The bond vigilantes are back

27.10.16

By Tom Startup

Falling government bond yields and rising prices have been with us for so long that it has come with a shock: since the Brexit vote on June 23rd and now the election of Donald Trump on November 8th, government bond markets have changed direction sharply. If bond yields continue to rise, bond investors could again act as disciplinarians on spendthrift governments – which means you, President-elect Trump and you, British Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond.

The reason for this turnaround, which has also affected euro area bonds, is simple: investors think that risk is back, and one of those risks is inflation. The 20% fall in sterling’s exchange rate since the Brexit vote is expected to lead to consumer price inflation rates of 2-3% during 2017, up from an annual rate of 0.9% in the latest month, while Mr Hammond has pledged to relax his predecessor’s policy of fiscal austerity regardless of a UK budget deficit that is still 4% of GDP.

Then along comes Donald Trump, pledging in his victory speech to introduce a big package of public infrastructure spending on top of his campaign promises to cut taxes on the richest Americans. If such proposals were to pass Congress – a big if – the result could be a boost to US economic growth just when its labour market is approaching full employment, which is a sure recipe for inflation.

President-elect Trump may not like to think back to Clinton-era advisers, but he would do well to remind himself of what James Carville famously said in 1993, when his then boss Bill Clinton took office with dreams of a big reflationary package: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

But will it do so now? The answer is that it will do so if governments take serious risks with inflation. And if the bond vigilantes do regain their power then two things will follow: the cost of servicing public debt will rise; and the next recession, when it eventually comes, is likely to be caused by the steepening of the yield curve, as long-term interest rates rise.

The surprise should be that it took so long. Ever since the 2008 financial crisis sent government debt levels soaring, financial markets have been gripped by a strange mood: almost everyone has said that public debts need to be cut yet bond yields have continued to fall, making borrowing cheaper than ever before. Only when there has been a serious default or currency risk – as with Greece in 2010, followed by other troubled euro sovereign debtors – have the bond vigilantes really hunted with their old force.

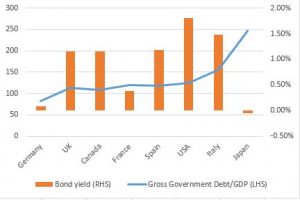

Back in 2010, when Greece revealed its budget deficit had reached 13% of GDP, its bonds were dumped, yields soared to over 40% and it was forced to accept a humiliating bailout from the EU and IMF. Subsequent massive cuts in spending and hikes to taxes have caused its economy to shrink by a quarter. But since then the bond markets have been remarkably quiet, allowing Western governments to continue to accumulate debt, without the vigilantes batting an eyelid. Across the EU and much of the West, levels of debt now regularly exceed 100% of GDP and yet until June yields remained below 2%. In Japan, where gross debt has reached 247% of GDP, nominal yields are negative. Even Greece, still struggling under the burden of debts that exceed 170% of GDP can borrow at rates of just 8%.

Source: OECD (2014), Bloomberg. Figures are gross government debt.

The question now is how tough the vigilantes will become. There are still reasons for bond yields to stay low. First there is the global savings glut – when world savings exceed desired world investment that money must be lent to finance current spending somewhere. This money, much of it from China, has found a home in the coffers of Western governments, happy to put off difficult decisions till tomorrow when they can have money to spend today.

Second, there is the now commonplace involvement of Central Banks in quantitative easing; the central banks of the US, UK, and the euro area have collectively bought around $5 trillion of government bonds, helping to sustain demand and keep yields low.[1] In Japan over a third of bonds (approx. $3.9 trillion) are now held by the central bank, which is buying two-thirds of new issues and thus in effect printing money to finance public spending directly.[2]

Third, inflation is still low, worldwide. Inflation is the bond-holders’ worst nightmare – destroying the value of his asset. But disinflation or deflation, now rife, is a bond-holders’ best friend, increasing his returns.

The point is that those factors now face some competition – or at least a significant amount of doubt. Rising inflation in the UK and the US could force central banks there to tighten monetary policy, especially if the inflation is accompanied by big fiscal stimulus programmes. The Federal Reserve Board may well raise interest rates in its December meeting. The Bank of England has recently expanded its quantitative easing to cope with Brexit, but could be forced to reverse that, especially as economic growth has already been unexpectedly robust.

The temptation for governments, even inside the euro zone, to go for growth is strong. The rise of populism has reflected high unemployment and disappointing wage rises, which governments, populist or otherwise, are going to feel obliged to try to counter. After years of deflation and disinflation, they sense that there is a lot of slack in the economy to be used up before inflation really starts to rise. They also know faster growth could help them lower their public debt to GDP ratios.

It promises to be quite a contest, between the urge for growth and the bond vigilantes. There is however one way to make growth likelier to win and the vigilantes to lose, or at least to delay: that is to liberalise economies, boosting competition, especially in Western Europe but also in the United States, for that will allow the supply side of the economy to react flexibly and rapidly to rising demand. The trouble is that the protectionism that President-elect Trump says he stands for would work in the opposite direction. It, like Brexit, promises to be a bumpy ride.

Edited by Bill Emmott

[1] Approximate figures: US: $3700 billion, US: $550bn then $85 bn, Eurozone: $600 billion.

[2] http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/10/13/business/financial-markets/boj-may-need-taper-bond-buying-stimulus-next-year-analyst-says/#.WBMWdiRtFG4

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: