From the blogs: Economists debate President Trump’s mooted fiscal expansion

26.01.17

![]() In this new weekly feature, we will highlight and explain debates on the economic blogosphere about current issues

In this new weekly feature, we will highlight and explain debates on the economic blogosphere about current issues

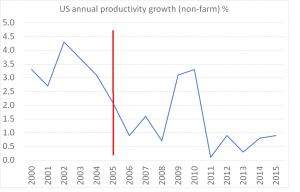

In 2005, George W Bush began his second term of office during a period of strong economic growth. He proceeded to cut taxes and increase government spending, while the housing market continued to inflate. The result was an economy that over-heated leading to higher interest rates, lower growth, and ultimately, the financial crisis of 2008/9. Twelve years later, and the election of Donald Trump, with his commitment to raise spending on infrastructure and cut taxes, raises the question of whether the US economy might face a similar fate this time round. This – beyond even the man himself – has sparked a lively debate about the suitability of Trump’s fiscal policy at this point in the economic cycle.

Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford) and Paul Krugman (Harvard), who were strong advocates of such fiscal expansion after the financial crisis, have come out against Trump’s planned tax cuts and loose fiscal policy. They both support new infrastructure spending, but oppose any additional net stimulus, e.g. through tax cuts. Their argument is that such fiscal expansion was appropriate, indeed necessary, after the financial crisis because the economy was far from full output and interest rates were close to the zero lower bound (ZLB). However now the economy is close to (if not at) full output and interest rates are rising, further stimulus would be counter-productive. As Krugman puts it:

“What changes once we’re close to full employment? Basically, government borrowing once again competes with the private sector for a limited amount of money. This means that deficit spending no longer provides much if any economic boost, because it drives up interest rates and “crowds out” private investment.”

Another critical voice is Menzie Chinn (Wisconsin-Madison), who has had a look back at the era of fiscal expansion under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. He shows that one of the main consequences was a ballooning current account deficit. If that were to happen again, there would be little economic gain from Trump’s plans.

Meanwhile Olivier Blanchard is more positive about fiscal stimulus. The former IMF chief economist, now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, argues that even if Trump’s fiscal stimulus leads to over-heating that might be beneficial in helping to overcome the labour-market problem known as hysteresis – in other words, he thinks a period of higher inflation and low unemployment might help draw back into the labour force some of the millions who left following the financial crisis, thus eliminating or delaying the achievement of full employment.

“Most likely, some workers who could not find jobs have become discouraged and are no longer looking for work. A period of very low unemployment may lead some of them to come back into the labor force. Thus, a larger fiscal deficit and some overheating may do some long-run good.”

It is certainly true that the labour-force participation rate in America has declined since the financial crisis, unlike that in Britain which has risen. However, it takes quite heroic assumptions to conclude that fiscal stimulus alone will reverse this trend in a substantial way. After a fiscal stimulus driven by tax cuts in 2005, the participation rate stayed pretty stubbornly flat, as the chart indicates. To change this might well require deeper interventions in social policy, retraining and other active labour-market measures, sustained over a long period.

Narayana Kocherlakota, a former member of the Fed committee that sets interest rates and now at the University of Rochester, has offered another argument in support of additional fiscal stimulus. He thinks that raising aggregate demand through extra fiscal stimulus may raise productivity, and if it does then we won’t hit the buffers of full output and GDP can rise without necessarily simply leading to higher inflation. As Wren-Lewis, who agrees with this line of argument, puts it:

“For example, a lot of technical innovations might have been shelved while demand was depressed, but would be brought into production if demand looked like expanding rapidly. As these technical innovations would expand the capacity of firms to produce more, they would not raise prices as a result of any increase in demand. “

Again, the comparison with the 2005 fiscal stimulus is not encouraging: then, with the economy similarly close to apparently full-employment and close to its potential output, productivity continued to slow despite the boost to demand. In any case, it is worth noting that Blanchard’s and Kocherlakota’s arguments contradict one another on this point: if Blanchard were proved correct, a new supply of low-skilled workers would be drawn in, potentially depressing productivity; on Kocherlakota’s argument, labour-saving automation would step in.

![]()

There are, of course, many differences between 2017 and 2005. China is no longer growing at 10% per annum, commodity prices are more subdued and the US economy does not appear to be in the middle of a property bubble. But other risks are present including the possibility of new tariffs and a trade war with China which if implemented would limit the potential growth of the US economy. There’s the difficulty in predicting, let alone analysing Trump and his intentions: is he going to prioritise a fiscal boost to the economy or trade retaliation against China? Well, we are about to find out.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: