Hammond throws the UK a modest cushion against Brexit

06.12.16

Phillip Hammond, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, is often depicted as dull and sombre but at November’s Autumn Statement he was positively chipper. Relaxed and up-beat, he even made a self-deprecating joke. And why not? After all, this is the man who has just ripped up his predecessor’s fiscal rules to cushion the economy against a possible economic shock from Brexit. Abandoning the attempt to achieve a fiscal surplus in this Parliament, he has chosen to borrow more to invest in infrastructure and innovation. Balancing the books can wait, so he says, until the next Parliament, and by then, after Britain has left the EU, it will probably much bigger things to worry about.

While the short-term impact of the reforms is being widely discussed, how will this affect the UK’s long-term economic performance? The UK’s position on the Wake Up 2050 Index is just nineteenth out of thirty-four. This is primarily due to long-term weaknesses in trade, debt, and inequality.

Trade

Britain’s trade as a proportion of GDP is half the level of Germany. With the largest current account deficit in the G7 this is a sign that British companies are failing to penetrate global markets. Brexit is only likely to make this worse, as unless the UK remains in the single market it will face increasing barriers to trade with its closest neighbours. Hammond’s answer, in advance of the Brexit negotiations, is to tackle productivity – a fundamental driver of our competitiveness – through a new £23 billion investment fund for infrastructure and innovation.

That makes sense: better infrastructure and more R&D will, in principle, make firms more productive and innovative. The question is whether it’s enough to make much difference. Since 2010 infrastructure spending has been slashed, and even with this new fund spending will rise from 0.8% of GDP to just 1-1.5% over this Parliament – still way short of the 3.5% recommended by the OECD. He is also doubling the financing available to support exporters. The overall benefit from that depends largely on whether or not Britain remains in the Single Market and on what trade arrangements it manages to negotiate with non-EU countries after Brexit.

Debt

This increase in public investment has implications for government debt. The UK’s government debt as a proportion of GDP, while higher than that in Germany, is still lower than that of France or the US. Now Hammond has relaxed the fiscal rules, replacing the target of a budget surplus by 2020 with a forecasted deficit of 2% of GDP. The result will be national debt rising faster than previously expected. It is now projected to rise to 88% of GDP by 2019/20 rather than the 77% projected in March. Such a rise in debt, if spent in the right areas, and leading to a higher growth rate is probably affordable, particularly when government bond yields remain at just 1.5%. But Brexit and the prospect of further increases in bond yields mean the government must tread carefully.

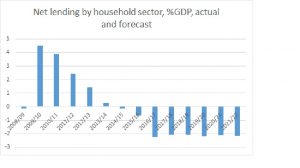

Probably a more worrying implication is for household debt. Britain’s households are already heavily indebted. Debt as a proportion of disposable income, at 150%, is higher than in either Spain or Greece. After the financial crisis households, sensibly, borrowed less and saved more. But once again household borrowing has been fuelling recent economic growth. Now further cuts in public spending and weak rises in take-home pay are expected to cause households to borrow even more than they were in 2008/9 (see Chart).

Note: a minus figure indicates borrowing. Source: OBR, http://budgetresponsibility.org.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-november-2016/, Supplementary table 1.10.

This combination of rising public and private debt is potentially toxic. If Brexit negotiations falter, or bond vigilantes turn against the UK then the economy could be hit by rising interest rates which hit households and the government simultaneously. With monetary policy already close to the zero lower bound, there would be few options left to prevent a serious recession.

Inequality

The UK economy is also marred by excessive inequality. Although income inequality has been mostly stable since 2010, it remains the worst in Europe. The fact that it hasn’t worsened seems mostly due to higher rates of employment and a financial crisis that cut the incomes of the better-off. Some of Hammond’s announcements could help, such as the 4% increase in the national living wage. But others, such as raising income tax personal allowance and higher rate threshold disproportionately benefit the rich. Planned cuts to benefits and universal credit will also hit many poor households hard. The government’s own analysis suggests the reforms in this Parliament will hit the incomes of the bottom 30% hardest. Inequality is set to worsen. This will act as a drag on the long-term growth rate, as richer groups save more than the poor.

Hammond’s first Autumn Statement (and his last, since he has just abolished this annual ritual) is an attempt to change the course of economic policy. Although still hemmed in by his predecessor’s austerity, and the threat of Brexit, the supposedly dull Chancellor has already surprised his detractors. The new investment fund is a modest step in the right direction towards raising productivity. However, it won’t be enough to tackle the trade imbalance if the Brexit negotiations result in a poor deal for the UK. The increase in borrowing is probably affordable, particularly as it is being used to finance investment. But Hammond hasn’t reversed the policy of tax and benefit cuts which threaten to worsen inequality and increase household debt. Because of this, the long-term implications of the Autumn Statement are not nearly as sunny as the Chancellor’s new demeanour.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: