Housing in Britain and America: The economic cost of NIMBYism

26.05.17

In recent years, major economies have proved to be tightly entwined with the fortunes of their countries’ housing markets. The financial crisis of 2008/9 had its epicentre in the mortgage market of the US, where financiers never thought a nationwide market crash was possible. In the UK, the last three major recessions were all associated with crashes in the housing market. Despite recent declines, around two-thirds of households still own their own home in both countries, typically through a mortgage, so homeownership creates a powerful economic link between the financial markets and the wider economy.

While housing markets in the US and UK appear to have recovered from the desperate days of 2008/9, economists are once again highlighting the increasingly dysfunctional nature of these markets, and their impact on the wider economy. One area that has received attention is the failure of house-building to respond to high prices, often exacerbated by NIMBYism – the tendency of homeowners to oppose new developments in their area.

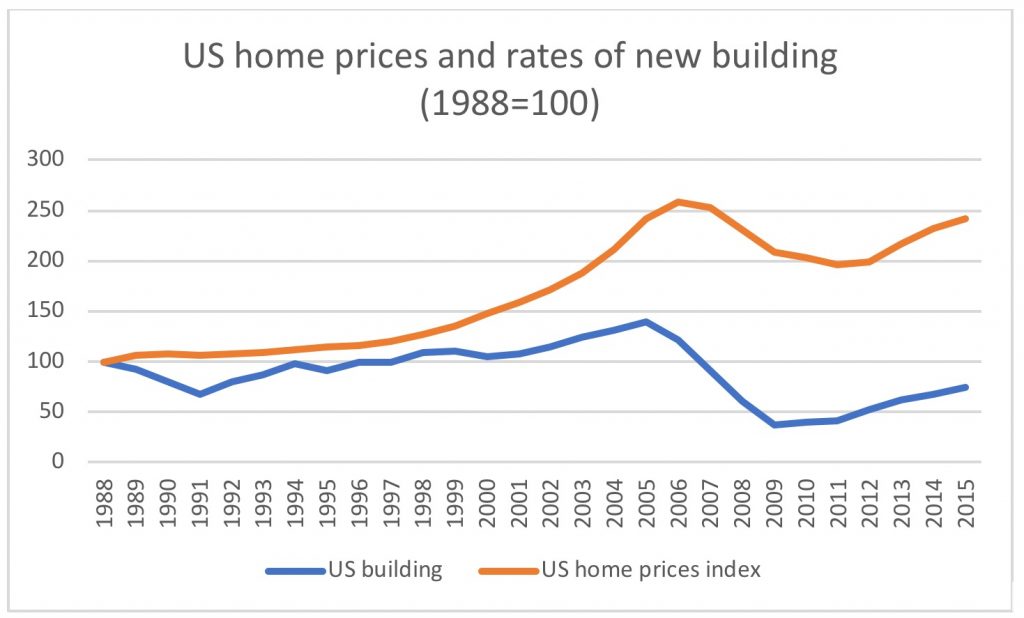

Scott Sumner, an economist at George Mason University, argues that although prices have been rising steadily in the US, the supply of new housing has not responded significantly. We can see this by plotting US home prices against rates of new building (See Chart). Average home prices in the US are now close to their pre-crash highs, but home-building rates remain significantly lower than their pre-crash norms.

Source: HUD, Case-Shiller National Home Price Index.

Sumner thinks this is due to a combination of lack of finance, NIMByism, and shortages of construction workers. His conclusion:

“The fact that construction is at a low level today, with the same real housing prices, indicates a massive adverse supply shock has hit the home construction industry. The buyers are there, the prices are good, the inventories are low—it’s just that America “forgot” how to build lots of single family homes.”

In other words, the financial crisis and its aftermath has had a kind of “scarring” effect on the housing market; the industry lacks the capacity to expand and meet demand, partly due to changes in government policy.

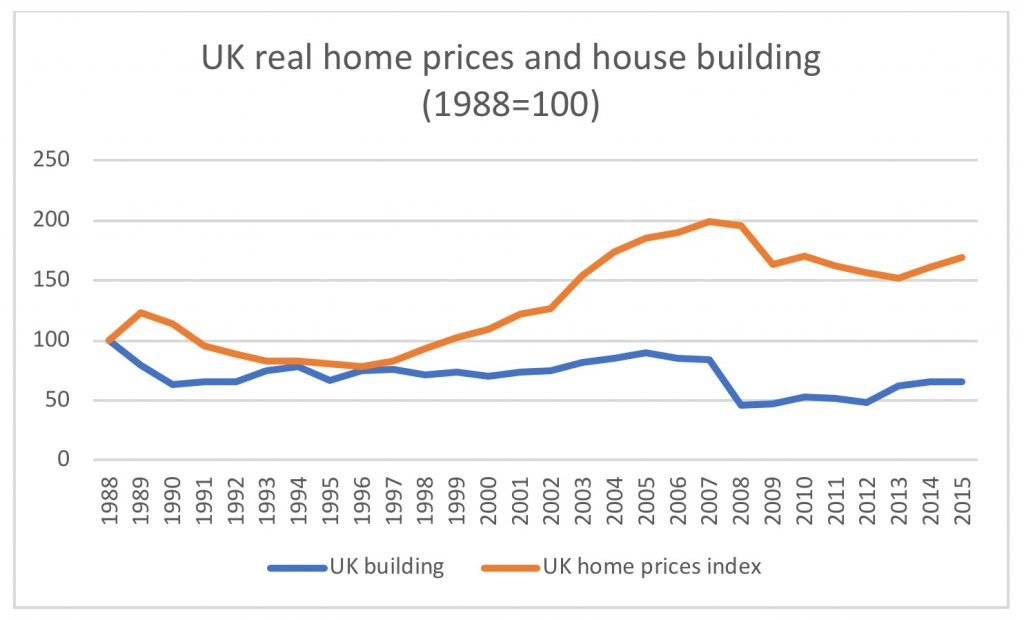

This also seems to be true in the UK, where despite record prices, house-building rates remain way below pre-crash levels. (See Chart)

Source: Nationwide, ONS.

John Plender, a veteran writer at the Financial Times, has diagnosed the underlying cause as a nefarious contract between politicians and house-building firms. Politicians know that getting re-elected requires them to protect the housing wealth of their electorate, so they have little interest in increasing supply. They therefore avoid relaxing planning rules but instead offer schemes like Britain’s recent “Help to Buy” which simply increase demand. At the same time house-builders can increase profits by simply owning land:

“This has facilitated a business model in housebuilding that relies heavily on constantly rising land values. Builders have had no great incentive to increase supply, which is one of the reasons why the number of housing starts always lags behind the grant of planning consents. Many have operated, in effect, as land speculators with a building operation on the side.”

But at what cost? Does it really matter if housing supply is constrained? On this question, a trio of recent academic papers suggest the costs are may be very heavy indeed. A paper by Ed Glaeser and Jo Gyourko, economists at Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania respectively, suggests that the costs of restricting supply, particularly in cities, significantly outweigh the benefits, and might represent up to 2% of GDP per annum for the whole economy. Another paper, by Andrii Parkhomenko of the University of Barcelona, tries to analyse the effect of restricted supply on productivity and the location of workers, and also estimates a cost of around 2% of GDP. A third paper, by Chang-Tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley, provides perhaps the most alarming conclusion. They suggest that restrictions on housing supply in the US might have lowered US growth by more than 50% between 1964 and 2009. This is because supply restrictions prevent workers from locating in areas where they could be more productive. If so, then NIMBYism, rather than a minor economic niggle, might be one of the most significant challenges Western economies face.

So, what should be done? Noah Smith, an economist and writer for Bloomberg, suggests that the solution is to build more homes and reform property taxation:

“Making it easier to build housing, as California is now trying to do, is one response. Essentially, the attack on Nimby-ism represents an attempt to return to the older model of accommodating local economic booms by building more housing. But there are other options available. One of the most interesting is the so-called Henry George tax or land-value tax, named after the 19th century economist Henry George. The idea is to tax land itself without taxing the development of the land — basically, a property tax with exemptions for buildings.”

The problem with an agenda of liberalising house-building, attractive though it is in many ways, is that it might lead to an even bigger boom and bust in the housing market. In countries where such regulations were light, such as Spain and Ireland, the housing boom and bust was even worse than elsewhere. During the boom, teenagers dropped out of high school because they could make easy money working in construction, while productive investment was diverted into buildings that turned out never to be occupied. After the bust, millions of homes were left unsold and empty; these ghost towns created a legacy of bad debts for banks, lost productivity and blight for many areas, which persists to this day. In contrast, Britain’s housing market, where building is more tightly regulated, recovered more quickly.

Housing markets are particularly problematic. This is because houses are simultaneously consumer goods which impose significant externalities on others, a vehicle for our savings, and the object of financial speculation. NIMBYism is an understandable attitude, not only as a way of preventing unsuitable construction but also as a way of protecting what is for most people their main store and source of wealth. But if it is costing economies up to 2% of their GDP every year, that is too high a toll. Increasing house-building, particularly in inner-city areas, is probably necessary. But governments need to be cautious about fuelling yet another unsustainable boom and bust. A difficult balancing act.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: