The end of austerity?

21.06.17

Taking stock of Britain’s experiment with fiscal austerity

Was it austerity that cost them the election? The surprise failure of the Conservative Party to win an overall majority in the British general election has been attributed to many things, including Theresa May’s demeanour, a gaffe over social care, and Jeremy Corbyn’s mobilisation of younger voters. But Nick Timothy, May’s former Chief of Staff who had to resign over the failure, suggests that many British voters were simply “tired of austerity”. For some, the appalling deaths at Grenfell Tower epitomise a government that has endangered the poorest in its ideological pursuit of a lower budget deficit. Others think that the government’s fragile position in parliament anyway must mean the end of austerity. So what is the legacy of austerity? And is now the time for it to end?

Austerity began in 2010 when in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis the UK budget deficit had ballooned to over 10% of GDP, and the sight of the Greek economy imploding due to excessive government debt served as – or was used as – a warning. The newly elected coalition government under David Cameron introduced a programme of cuts in public spending with the aim of eliminating the deficit by 2015. Welfare benefits were cut, public sector pay was capped, and public investment was slashed. The budget deficit began to shrink, but more slowly than expected due to a weak economy and subdued wage growth.

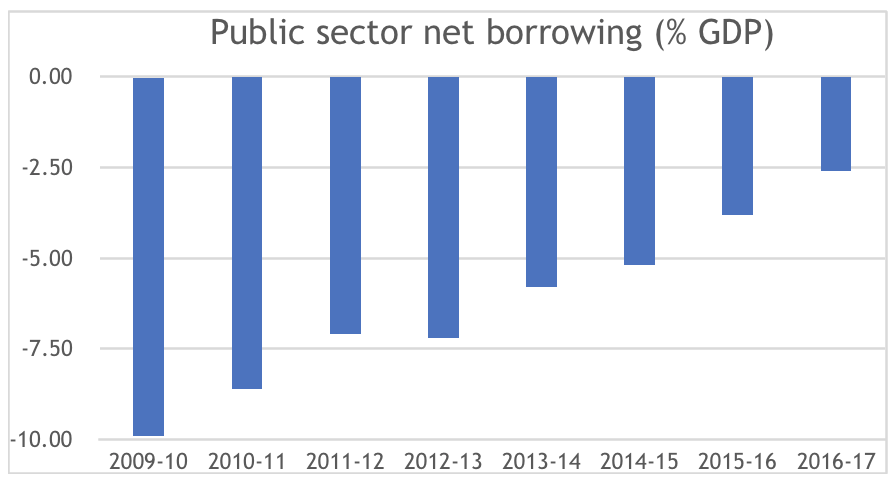

Then last year Britain’s decision to leave the EU prompted the new Chancellor, Phillip Hammond, to push back the deadline for eliminating the deficit to 2025. Now, with an economy seemingly close to full output, the deficit remains over 2% of GDP (See Chart). The failure to eliminate the deficit, coupled with weak growth and increasing strains on public services, has arguably cast doubt on austerity’s rationale in the first place.

Source: OBR.

Now Nicholas Macpherson, the former Permanent Secretary at the Treasury, the department responsible for implementing austerity, has written a partial defence of the programme. Controversially, he argues that because public debt as a share of GDP has continued to rise “Britain never experienced austerity”. He also thinks that further austerity will probably be needed:

“With interest rates at a historic low, a case can be made to borrow to invest more in infrastructure and housing. However, the pressures that are now upon us are not about investment, but public consumption. We are already running one of the biggest structural deficits in Europe, and Britain’s debt is at its highest level in relation to national income since 1964.”

But Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation, a think tank, believes the true meaning of austerity lies in cuts to public spending, not the level of the national debt.

“But for the public, austerity was never just about public borrowing figures, it’s much more about actual policy decisions – specifically spending cuts. A growing economy and tax rises can also cut the deficit, but austerity in the public mind is principally about reducing public spending – be that cutting public services, the wages of public servants or welfare payments.”

So, he argues, if we want to know if austerity is finished, we should wait to see if the government lifts the cap on public sector pay and the freeze on benefit payments.

Simon Wren-Lewis, an economist at Oxford University, also takes issue with Macpherson’s account. On the idea that we “never experienced austerity” because of a rising level of national debt, he is scathing:

“The statement confuses levels with rates of change, whether you are talking about the impact on the economy or on individuals. This is first year undergraduate stuff.”

He also disputes the idea, suggested by both Macpherson and Phillip Hammond, that a deficit of over 2% of GDP is unsustainable:

“To work out roughly what the sustainable deficit is, divide the debt level by 100 and multiply that by the expected growth rate of nominal GDP. That means that today a deficit of 2.5% of GDP would be sustainable as long as nominal GDP grew at about 3%. So his statement that a deficit of 2.5% is not sustainable simply looks wrong.”

Wren-Lewis has argued elsewhere that the lower growth caused by austerity means that the average UK household is now a cumulative £4,000 worse off than they would have been without it.

Ben Chu, of the Independent, tends to agree. While accepting that there was a case for reducing a deficit of 10% of GDP, the continual pursuit of austerity, despite the evidence that it was harming the economy and public services was, he argues, grossly irresponsible:

“Reducing the UK’s deficit, which had ballooned to 10 per cent of GDP in 2010 due to the financial crisis, was a necessity. Cutting it without regard for the state of the overall economy and the feedback effects on aggregate demand was unscientific stupidity and wanton vandalism. Austerity, as practiced by the Conservatives, was a policy driven not by economics, but by politics and ideology.”

Martin Wolf, of the Financial Times, considers the longer-term outlook for the public finances. He distinguishes between the arguments for reducing the deficit and those for cutting spending further. In his view, the UK should still attempt to do the former, but not necessarily the latter. The argument for further cuts in the deficit is:

“It makes sense to run a still smaller deficit when debt is high and the economy is close to full employment. The aim would be to insure against any shocks that lie ahead, by reducing the debt ratio.”

His conclusion is that spending can rise, but so too must taxes if we are to put the public finances on a sustainable trajectory in the long-run.

Seven years on, it is easy to forget the atmosphere of fear, bordering on panic, engendered by the financial crisis and bank bail-outs after 2007-08. The decision by the UK government to cut the deficit was an understandable (if not inevitable) response to the real possibility of a bond market rout. However, the academic consensus is now clear that the cuts in spending depressed growth and delayed the economic recovery, even leading to rises in the public debt-to-GDP ratio. And the choice to cut public spending on benefits and public services (while financing tax cuts and protecting pensioners) was neither rational nor inevitable – but, as Ben Chu argues, an ideological decision. The term “austerity” has been used to systematically confuse the question of whether to cut the deficit with whether to cut public spending – which, as Martin Wolf argues, are logically distinct. So, whatever we decide to do with taxes and spending in the future (and it is a political choice not an economic necessity), we would be better off jettisoning this dangerous term.

By Tom Startup | 22/06/17

Edited by Bill Emmott