The end of the beginning of Brexit

30.03.17

As the UK triggers its withdrawal from the EU, economists debate its likely impact

“Now is not the end. Nor, indeed, is it the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps the end of the beginning.” As the United Kingdom prepares to withdraw from the European Union, the words of Britain’s war-time leader, Winston Churchill have a curious resonance. It is now nine months since Britain voted, by a margin of 52% to 48% to leave the EU. Since then the economy has surprised many by growing more strongly than expected, while the debate has been dominated by what our future relations with the EU will look like. With the triggering of Article 50 yesterday, Theresa May has now formally begun the two-year process of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union. This has prompted some renewed discussion about its likely economic implications.

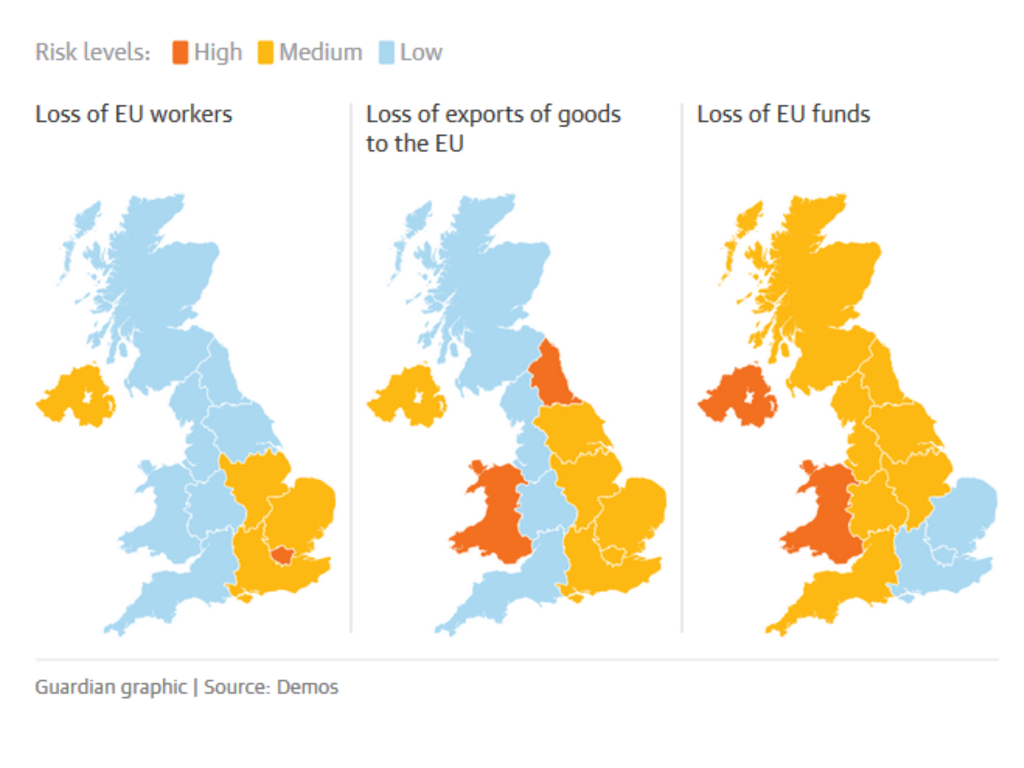

New research from independent think tank Demos (to which your present author contributed) highlights how a hard Brexit might play out across the UK. Analysing the reliance of different parts of the UK on EU labour, exports and EU grants, they find that the risk to Wales, Northern Ireland and the North East are particularly serious (see maps). Ironically, Wales and the North East voted to Leave, despite their dependence on EU funds. In their analysis of the risks to different sectors they find that manufacturing and agriculture are particularly vulnerable because of their reliance on EU labour, trade with the EU and the potential magnitude of future tariffs.

To avoid some of these implications, one option the government could pursue is a form of associate membership of the customs union, so that the UK can still sell its goods into the EU without additional transaction costs. On that matter, Open Europe, a Eurosceptic think-tank, argues that we would be nevertheless be better off out, because of the limits it would place on the UK forming trade agreements with non-EU countries. Aarti Shankar, one of their analysts said:

“We have looked at the evidence and at international examples, and conclude that leaving the EU’s customs union is the right decision for the UK. If the UK remained in the customs union after Brexit, it would not be able to meet the government’s ambition of conducting an independent trade policy and achieving a truly ‘Global Britain’.”

Sam Bowman, of the Adam Smith Institute, a free market think-tank and consultancy, has had a look at the implications of Brexit for Ireland. This is a particularly thorny issue since the Republic will remain a member of the EU while the North, as part of the UK, will leave, creating new problems about the border between the two. While pointing out that UK-Irish trade is less significant than it once was, he can’t see any alternative to border-checks for goods:

“Customs checks are a bigger problem, and may prove to be quite costly for the Irish and British economies. Even with a very comprehensive free trade deal, it is likely that UK exports will be subject to ‘rules of origin’ checks by the EU. These checks are designed to prevent people by-passing tariffs by moving goods through middleman countries with low or no tariffs between both the origin and destination countries.”

They also envisage the possibility of Dublin poaching financial firms that are looking to relocate – something the FT has shown is increasingly likely.

Larry Elliott, a Leave-supporting columnist at the Guardian, considers where the UK might end up after two years’ negotiating. Citing Pascal Lamy, former head of the World Trade Organisation, he argues that the UK might be able to get a free trade deal with the EU but it would take five or six years. That would make the two-year Brexit timetable far too short, requiring some sort of transitional arrangement. But a major sticking point is likely to be the EU’s product standards. For goods to move freely between the UK and the EU we would have to accept the same product standards (regulations) as the rest of the EU – but crucially, without us having any say over them. Elliot thinks the UK public might still accept that loss of “control”:

“The UK government, for its part, would have to consider whether such a deal would be sellable to the public. It probably would be. Brexit happened because of concerns about immigration not because voters wanted the freedom to have dirtier beaches or less safe nuclear power stations.”

But what evidence is there on what the British people actually want? The Economist has a blog about the latest survey data on attitudes towards the various possibilities involved in soft and hard Brexit. It seems, not surprisingly, that people want to have their cake and eat it. Such survey questions do not give much, if any clue about priorities and trade-offs. More specifically, while 90% of voters (whether Leave or Remain) favour free trade, a clear majority of both also favour customs-checks on goods and people from the EU – the antithesis of free trade. And while people support some EU regulations – on beach cleanliness and roaming charges – they dislike others e.g. on the use of pesticides by farmers. One thing we can be sure about is that a lot of people are not going to get what they want.

The EU is not perfect. Its policies on agriculture and fisheries are often wasteful and inefficient. Some of its regulations are unnecessary and onerous. The creation of the euro may not have been in the best interests of all its member states. But, over the course of sixty years, by creating the conditions for the peaceful co-existence of nations and a gradual liberalisation of markets, it has probably done more than any other institution to promote openness – a crucial driver of long-term prosperity. British politicians and the public, understandably, like some parts of the EU and not others. But in the Brexit negotiations, we won’t be allowed to cherry-pick the bits we like and reject the rest. That realisation, which may only dawn slowly, will have significant economic and political ramifications, for years to come.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: