The inequality that helped Trump win could now get worse

16.11.16

By Tom Startup

Was it the economy that won it? On the face of it, it wasn’t immediate economic woes that pushed Donald Trump into the White House. He inherits an economy that, if not in rude health, can still be said to be humming. With unemployment close to pre-crisis lows of 4.9% and wage growth at 4%, US voters, it would seem, had little to complain about. When Trump supporters were asked why they liked him, just 10% mentioned economic policy.[1] But this bright sheen masks darker undercurrents that partly explain the rise of Trump and threaten long-term prosperity. On the Wake Up 2050 Index, the US is ranked in 22nd place, partly due to its extreme levels of inequality.

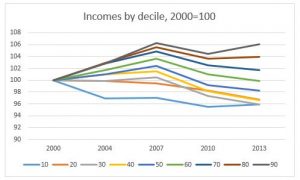

Recent economic growth in the US has disproportionately benefited the rich (See Chart).[2] Since 2000, the bottom half of the income distribution have got poorer, while the rich got richer, with the very richest doing best of all.

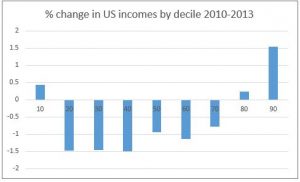

Even under the Obama administration the pattern has barely shifted. While the very poorest have at last seen their incomes rise, the middle 60% saw big falls while the top 20% gained disproportionately.[3]

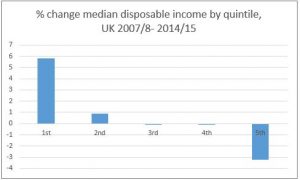

This contrasts strongly with the UK (see Chart below). There, income growth since the crash has disproportionately benefited the poor, with the rich losing out and middle income groups treading water. Poorest groups benefited from higher employment, as well as some welfare-benefit payments. But the better-off, many of whom worked in the financial sector, saw their earnings decline after the financial crisis hit.

The economic growth the US economy is generating is simply not benefitting large swathes of its population. When Donald Trump said that “The American worker is being crushed”[4] we might have dismissed this as hyperbole, but, for the millions of workers who have got poorer over successive governments, he has a point. Nor should we be surprised that, while he did best among richer groups, there was a 16% swing to him among Americans that earn less than $30,000.[5]

America has long had a higher tolerance for inequality than other nations, but plainly there are limits. Inequality means that the economy is not serving the growing needs and wants of a large proportion of the population. High levels of poverty mean workers are likely to suffer ill-health and be less productive. It may also reduce overall growth as the wealthy save more than the poor, depressing consumption. As the poor seek to sustain their living standards through the accumulation of debt, financial instability may worsen. Politically, it’s dangerous too. High levels of inequality undermine democracy by skewing political power towards the ultra-rich. Meanwhile the increasingly desperate majority are tempted towards ever more extreme parties and candidates in the hope of improving their lot – as we have just seen.

Why is American inequality getting worse? Deindustrialisation and mechanisation are partly blamed for the loss of well-paid manufacturing jobs. But those forces are at work across most Western countries. Mostly it is to do with government policies which penalise the poor and reward the rich.[6] Rates of income taxes and government welfare spending are low by international standards, while protection for employees is relatively minimal. Levels of competitive intensity in the US economy have fallen in recent decades and industrial concentration has risen, thanks to a boom in mergers and takeovers and deliberately lax antitrust enforcement. This has helped further shift income away from labour and towards capital – ie the rich.

What are the chances of reducing inequality under the Trump administration? Given that Republicans now control all three main arms of government, in theory the prospects of introducing large-scale economic reforms are better than they have been for many years. Moreover, inequality and a sense of unfairness are what have put Trump in the White House, so he ought to be motivated to do something about them.

Yet the political instincts of Trump and the Republican party to not argue for optimism – at least if their promises are taken at face value. Trump’s stated economic policies include cuts in income taxes, business taxes and inheritance taxes and a repeal of Obamacare, the health-care reform by his predecessor which did at least something to help the poorest. He has also pledged to scrap the Trans-Pacific trade deal, renegotiate (or scrap) the North American Free Trade Agreement and introduce new punitive tariffs on Chinese imports.

How would this affect inequality? The answer is clear – they will probably make it worse. Such tax cuts mirror those of the Reagan era which resulted in inequality soaring. Erecting tariff barriers might have some short-term benefits, helping to protect demand and incomes in some of America’s ailing industries such as steel and car production. But the longer-term effects are grim. Inflation will rise, eating into the take-home pay of ordinary Americans. Higher costs for businesses will encourage, rather than discourage, the relocation of employment overseas. It’s hard to see how this can help raise the incomes of ordinary Americans.

Trump as president may prove a different figure from Trump as candidate. He had better do, if there is to be any chance of healing his country’s deep economic divide. Otherwise the cure the American people have prescribed for themselves would just make the illness worse.

Edited by Bill Emmott

[1] http://www.people-press.org/2016/09/21/in-their-own-words-why-voters-support-and-have-concerns-about-clinton-and-trump/campaign_1/

[2] Source: https://ourworldindata.org/incomes-across-the-distribution/ Author’s analysis.

[3] Ibid, Author’s analysis.

[4] http://money.cnn.com/2016/03/15/investing/donald-trump-trade-oped/

[5] http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/11/08/us/politics/election-exit-polls.html

[6] http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/17/opinion/inequality-unbelievably-gets-worse.html

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: