Who are the winners and losers from a universal basic income?

08.06.17

Mark Zuckerberg likes it. Elon Musk is a fan. Even the new French President, Emmanuel Macron, is open to the idea. The idea of a universal basic income (UBI) – an unconditional cash payment to all households, regardless of their economic circumstances – is one of the hottest political ideas of our time. And it is moving closer to becoming a reality as governments across the globe seek new ways to reduce poverty while saving money. Finland is experimenting with it, the EU is funding pilots in Barcelona, Utrecht and Helsinki, and it is in the manifesto of the British Green party for the imminent UK general election.

An idea dating back to at least Thomas Paine, it commands support from both the left and right of politics. For the right, a UBI promises a dramatic simplification of an (often despised) welfare state. A myriad of complex, overlapping, benefits and subsidies would be replaced by a single cash payment, allowing individuals to support themselves without distorting market forces. A UBI sought to be easy and relatively cheap to administer, compared with means-tested benefits. It should improve incentives to work, as the income would not be withdrawn from the unemployed as they move into work.

For the left, the UBI fulfils the idea that citizens should be entitled to a share of the proceeds of the economy at a level that lifts them out of poverty. By removing the fear of unemployment from workers, it should, they argue, create the conditions for them to press for higher wages and better working conditions.

For the likes of Zuckerberg and Musk, the economic circumstances of the 21st century have created a new argument: that it’s the only way to protect workers from chronic insecurity and anxiety in a world where technological advance may replace their jobs, or render their labour worthless.

Critiques have usually focussed on the cost of the scheme. Because a UBI is paid to everyone regardless of their income, the implications for tax rates are potentially eye-watering. The economist John Kay has attempted to work out how high the tax rate would have to be to provide a level of basic income that would be acceptable to its advocates. Looking at the potential for a modest basic income in the UK, he finds that:

“For example, basic income at 30% of median earnings would require an increase of ten percentage points, from 40% to 50%, in the implied average tax rate. To set a target of 40% of median earnings (still below most judgements of a reasonable minimum wage) would require all existing tax rates to be increased by more than 20 percentage points (i.e. 50%).”

In other words, a basic income that had any hope of reducing poverty would require an enormous increase in taxes. He thinks that to save the idea of the basic income it would be necessary to restrict it in various ways – for example, providing it to children at a lower rate, making it relative to housing costs, and so on. But if we did that we might very well end-up with a welfare system that looks much like the messy one we already have.

Kay says that “While the details of such calculations would vary from country to country, the essentials remain the same, and the conclusions inescapable.” Now the OECD has carried out an analysis of the potential implications of a UBI in four countries, Finland, France, Italy and the UK, and interestingly, the conclusions do vary somewhat depending on the country.

The authors model the impact of abolishing most working-age benefits and tax-free allowances and replacing them with a revenue-neutral UBI (subject to income tax) set at the level of income currently guaranteed in the benefits system. One of the main effects is to raise the incomes of couples without children while reducing the incomes of single parents. (This is because existing social security systems tend to give more money per person to single parents than couples with children, and give more to families with children than those without.) It’s not clear that that is a desirable outcome – when single parents are at much greater risk of poverty than couples without children.

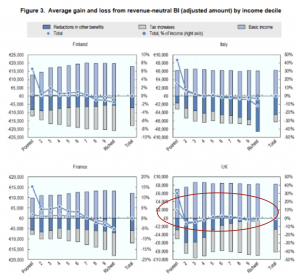

They also find that the impact of the scheme depends on the nature of the existing welfare state (see charts).

In the UK, where most benefits are means-tested, and therefore take-up is low, the very poorest would stand to benefit from a UBI. But above that level, low-income groups would tend to suffer because the OECD reckons the UBI would not be sufficient to outweigh the loss of means-tested benefits. Contrastingly, in Italy, France and Finland, where current benefits are either poorly-targeted or already universal, the OECD reckons a UBI would be generally progressive – raising the incomes of the poorest while reducing those of richer groups. So perhaps the case for a UBI of this kind is stronger in those countries than in the UK.

Dylan Matthews, a writer for Vox, has commented on a recent report by the American Enterprise Institute, about the feasibility of a revenue-neutral basic income for the US. The study examined the impact of replacing cash-transfers as well as Medicare, Medicaid and social security for retirees with a basic income. They find that, on average, this would benefit the middle class and those of working age at the expense of the poor and the elderly. Matthews:

“By contrast, more or less everyone over the age of 65 would lose out — big time. The poorest seniors would lose more than $34,000 worth of benefits in exchange for the UBI. Low- and middle-income people would lose $18,000 to $28,000 each. The rich would lose out for the same reason poor non-seniors would.”

For Matthews, these problems suggest that basic income is flawed– and that a negative income tax (where transfers are withdrawn progressively) is a superior concept.

This scepticism about the distributional consequences of a UBI is backed up by a new study from Luke Martinelli, a Research Associate at the University of Bath. He examines the likely effects of three different versions of UBI on UK households. If the scheme is designed to be revenue neutral then groups such as lone parents, single pensioners and the disabled would suffer large falls in income, relative to current provision. So the scheme might improve incentives to work for other groups, but at a hefty price in terms of poverty.

The welfare states of most Western countries are far from perfect. Perverse incentives, excessive complexity, and poorly-targeted handouts are a frequent problem. The objectives behind the UBI – of reducing poverty and economic insecurity while increasing the incentives to work and innovate – are therefore admirable. But any policy that unites thinkers on both the libertarian right and interventionist left should ring alarm bells. These latest studies show that a UBI might improve the incentives to work for some groups, but, for most countries at least, poverty for lone parents and pensioners would worsen. In welfare provision governments seem to be stuck with a kind of trilemma: one can reduce poverty and preserve incentives to work, but only at great expense (Finland); or one can reduce poverty and keep the cost down, but undermine the incentives to work (UK); or one can keep the cost down and preserve incentives to work, but have little impact on poverty (US). The UBI attempts to dodge this trilemma, but ultimately fails.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: