Why does inequality matter?

27.04.17

Economists debate whether all that matters is poverty

Economists are ambivalent about inequality. This is because they find themselves torn between two powerful ideas. On the one hand a simple argument for lower inequality is based on the idea of diminishing marginal utility. As my income increases, my happiness increases at an ever slower rate. In happiness terms, £1 is worth much more to poor people than it is to the rich. So, excessive inequality reduces welfare, concentrating in the hands of the rich money that makes almost no difference to their lives, while the poor live in misery. Government should therefore intervene to redistribute money from the rich to the poor.

The trouble is that this simple idea clashes with how most economists think wealth is created – through the operation of free markets, the consequence of which is huge variations in income and wealth. The ‘answer’, for most economists at least, has been to advocate government efforts to ameliorate the position of the very poor, while allowing capitalism an otherwise free rein. Call this the ‘poverty-first’ approach.

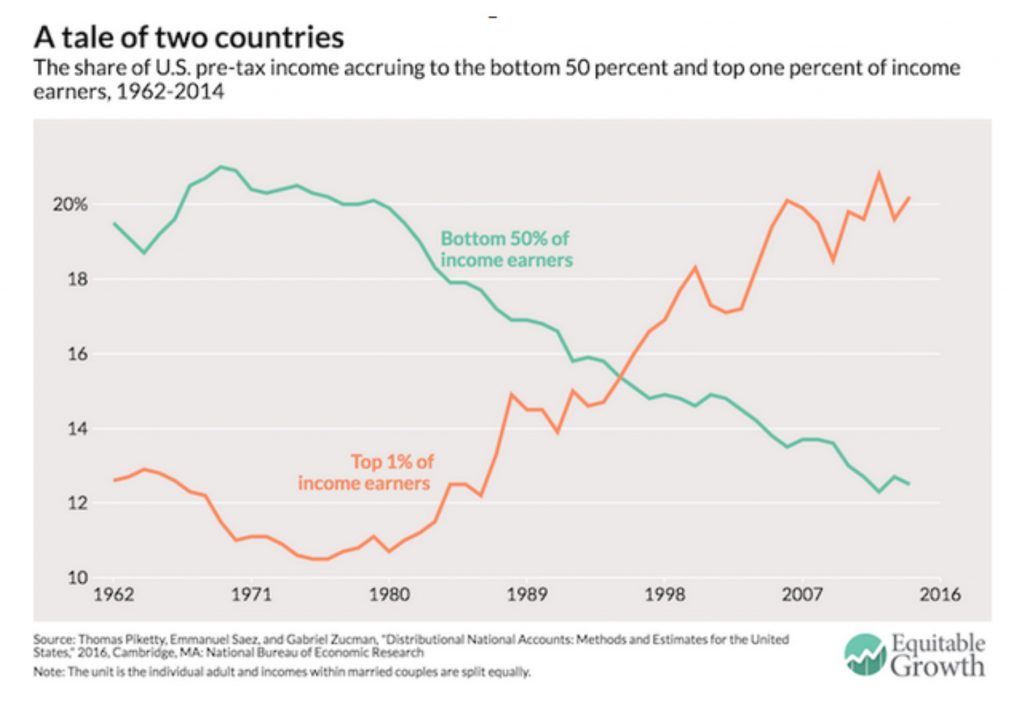

In recent years, the ‘poverty-first’ approach has been reflected in the policies of successive governments, particularly in the UK and the US. Clinton in the US and Blair in the UK accepted the idea, devoting their efforts (with varying degrees of success) to improving the lot of the poor, while, as Peter Mandelson once put it, being “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich.” The idea held firm for a while, but meanwhile, the incomes of the super-rich were stretching ever further away from the rest of the population (See Chart).

The financial crisis of 2008/9 hurt those at the top, but as many people got poorer, concerns about inequality rose to the surface. Then in 2013, a hitherto little known French economist published a book which propelled the topic of inequality back into the forefront of economics – Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. That book argued that global capitalism contained forces that were acting to raise inequality and would continue to do so unless constrained by global government action. Now, with the election of Trump in the US and Brexit in the UK, there is a renewed focus on what, if anything, governments should be doing about inequality.

Miles Kimball, an economist at the University of Colorado Boulder, has kicked off a debate by trying to revive the ‘poverty-first’ idea, based on the concept of diminishing marginal utility. Using survey data about people’s attitudes towards gaining or losing money, he develops a novel way of viewing the welfare value of money:

“Extending this idea throughout the full range of income yields something like the inverse square law for gravity, only a bit more dramatic: just as being ten times as far away from the Sun reduces the force of the Sun’s gravity by a factor of 100, being ten times richer reduces the value of an extra dollar by a factor of at least 100. And just as being ten times closer to the Sun increases the force of the Sun’s gravity by a factor of 100, being ten times poorer increases the value of an extra dollar by a factor of at least 100.”

He goes on:

“Thus, quantifying the idea that a dollar means more to a poor family than to a rich family shows that as far as financial well-being is concerned, inequality is about the poor, not about the rich.”

This way of looking at inequality, he argues, yields some interesting conclusions. It, he suggests, favours an open immigration policy. Since immigrants are relatively poor, lifting their incomes only marginally makes them much better off. This would still be so even if (for political reasons) we discount the welfare of immigrants relative to the general population. Less intuitively, he uses the idea to criticise minimum wages on the grounds that they exclude the very poorest from working, while often raising the wages of those further up the scale. Instead, Kimball argues, we should favour the use of the Earned Income Tax Credit (a form of means-tested income support for poor workers, used in the US), over minimum wages. Crucially, he thinks we shouldn’t be overly concerned about the ultra-rich since it is really the position of the poor that matters.

In the UK, where recent government policy has been to do more or less the opposite of what Kimball proposes, Simon Wren-Lewis, of Oxford University, thinks, on grounds of utility, we still need to focus on the position of the rich:

“The fact that the ultra-rich have wealth that is truly astonishing may not be an accident, but may be a result of exactly the same principle that Miles explores: diminishing marginal utility. The rich are no different from everyone else in wanting more utility, except for them it requires huge amounts of money to get it.”

This matters, because unless government takes action to suppress it, these people will do their very best to raise their incomes significantly, even if it’s at the expense of others. Citing a paper by Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva, he argues that the principle helps explain the consequences of cutting the top rates of income tax.

“with punitive tax rates, there was little incentive for CEOs or finance high-flyers to use their monopoly power to extract rent (take profits away) from their firms. It would only gain you a few thousands after tax, which as they were already well paid would not increase their utility very much. However once top tax rates were cut, it now became worthwhile for these individuals to put effort into rent extraction.”

If this is correct, then we can’t simply focus on the poor, as Kimball argues, but also need to work hard to prevent the better- off from engaging in harmful activities in the pursuit of that elusive extra utility.

Chris Dillow, an economist and blogger, agrees with Wren-Lewis that it’s about more than just the position of the poor, or the rich, but argues that inequality is about the middle class too.

“If the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting better off, then for a given level of income, somebody must be getting worse off. The “Blairite society” of super-rich but little poverty is one in which the middle class is relatively poor.”

Dillow’s argument is that if the ‘poverty-first’ approach means we redistribute from the rich to the poor, the rich will probably still thrive, but the middle class will (relatively) suffer. He also argues that since governments focused primarily on the position of the poor, at least in the UK, growth in living standards has slowed down. For Dillow then, the aim shouldn’t be to eliminate poverty, but to eliminate both poverty and extreme incomes:

“Miles might be right that it’s better to have a society of super-rich and no poverty than one in which there’s poverty and no super-rich. But this is a close call. And it omits a third option – a society in which there is both no poverty and no super-rich. It is this that we should be striving for.”

In other words, contra-Kimball, we can’t just focus our efforts on helping the worst off and remain ‘relaxed’ about the growing incomes at the top – particularly if the economic model is no longer generating general growth in living standards. The existence of the rich and the poor are both, in that sense, economic failings.

The ‘poverty-first’ idea was based on the belief that capitalism could generate rising incomes for all. If it did, then indifference about inequality could perhaps be justified in the knowledge that over time the poor and middle-class would get better-off too. But with the growing realisation– in countries such as the UK and US at least – that capitalism might fail to deliver those rising incomes, its justification is on thinner ground that it has been for decades. If, as seems possible, growth and living standards continue to stagnate, the pressure for much greater government intervention to cut inequality will, with good reason, become irresistible.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: