Would Martin Schulz dare to reflate and open up Germany’s economy?

28.02.17

News that the SPD – Germany’s socialist party – has overtaken the CDU/CSU in the opinion polls for the first time in a decade has galvanised the often sedate world of German politics. Under its new leader, Martin Schulz, former President of the European Parliament, the party is enjoying a remarkable surge in popularity. With federal elections looming in September, this raises the possibility that the seemingly unassailable Angela Merkel could finally be ousted after 12 years in office. That’s why eyes are now on Schulz for clues as to Germany’s economic future.

Early signs are not promising. While he is, so far, light on detail, he is raising the prospect of reversing some of the labour market reforms ushered in under former SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schroder. But, while politically appealing to his party’s core supporters, these reforms are the wrong target. Germany’s long term prosperity depends on addressing three areas: demographics, imbalances within its economy, and openness. So does the prosperity and stability of the whole European Union, the health of which is of fundamental importance to Germany.

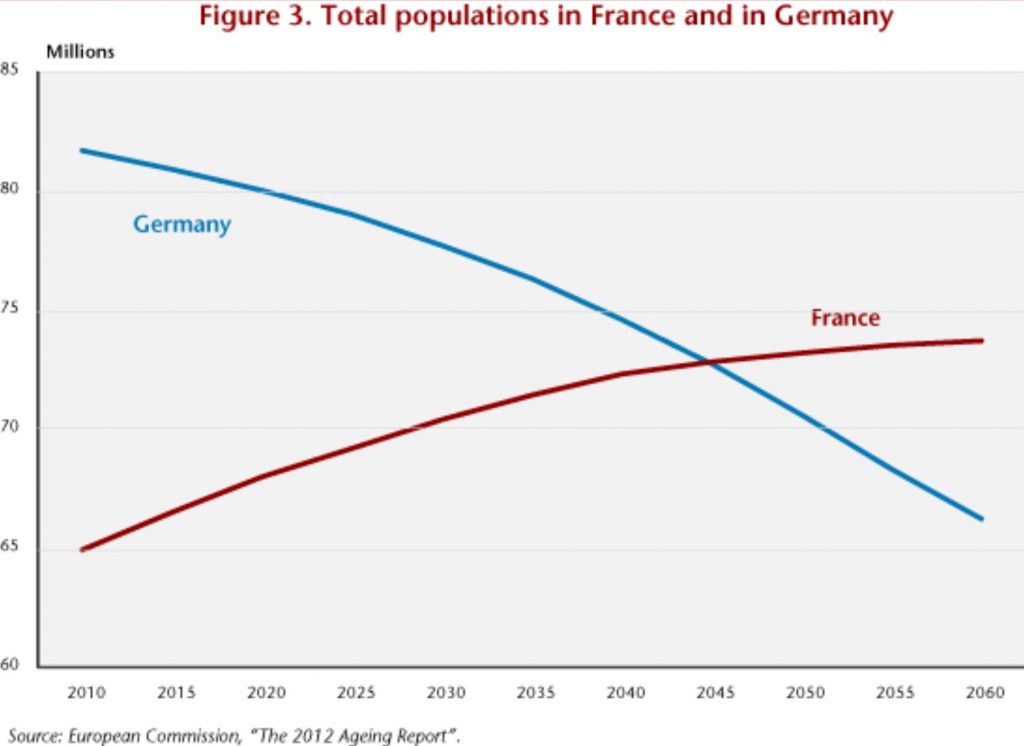

With a very low fertility rate Germany faces the prospect of a rapidly ageing society and declining population. On current projections, France’s total population will overtake that of Germany by 2050 (See Chart). That has fiscal as well as psychological implications. Germany already spends too much on public pensions – over 10% of GDP (similar to the level in Spain), and that is only set to rise.

From: http://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/blog/france-germany-the-big-demographic-gap/

From: http://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/blog/france-germany-the-big-demographic-gap/

In this context, Chancellor Merkel’s controversial move to allow over one million refugees to make their home in Germany last year may have been more than an act of charity. Mostly young and energetic people who will work and pay taxes for decades, these are exactly the sort of people Germany needs to plug its demographic deficit. But with German tolerance of immigration probably at its limits, the country urgently needs reforms in other areas. A review of pension entitlements and retirement ages, and greater support for families to raise the birth rate, is also needed.

The second major issue is Germany’s unbalanced economy. With its surplus hitting a record high, economic growth is still overly reliant on trade. While Germans view this as a matter of pride, and evidence of their manufacturing excellence, it has a darker side. It makes the German economy reliant on the consumption and investment of its trading partners – and therefore highly vulnerable to any external shock. During the financial crisis Germany’s economy was hit very hard due to the impact of US recession on trade and investment. It also means that German consumers and firms have high levels of savings, reducing their demand for the goods and services of their Eurozone neighbours, dampening economic growth in the whole region.

It is also creating unhelpful tensions with the US administration who increasingly view Germany’s trade position as evidence of currency manipulation. If not resolved this could lead to trade wars between the US and the EU. Germany needs to increase the share of its economy going to consumption and government spending, both for its own good and to improve relations with its own Eurozone members and important trading partners. It also has huge needs in infrastructure investment. This would mean reviewing the fiscal rules which currently constrain public spending and borrowing. It might also mean reducing the current rewards for saving (and the generosity of pensions).

The fiscal austerity policies beloved of Chancellor Merkel’s popular finance minister, Wolfgang Schaueble, need to be ended – but whether proposing to do so during an election campaign would be politically wise for Mr Schulz remains to be seen.

Lastly, Germany, one of the great manufacturing nations, could do more to open its economy, and more broadly, the Eurozone’s service sector. On the Wake up 2050 Index, Germany is less open than either Portugal or the Czech Republic. While it has been one of the driving forces behind the creation of a level playing field in the production and sale of manufactured goods across the EU, progress on something similar for the service sector has lagged far behind. Germany has retained complex licensing and occupational requirements in many areas which prevent other firms from entering its markets. Germany is thus a major obstacle to the development of the EU’s single market to take in the activities that make up the vast bulk of all modern economies.

This is probably one reason that Germany’s foreign inward investment is much lower than comparable nations such as Denmark or the UK. Germany, like France, has often resisted the creation of a ‘service sector passport’ – a right for EU firms to sell their services in other EU countries – due to concerns about a loss of standards, often under pressure from powerful trades unions. These barriers to openness not only hinder Germany –even its economy is 70% services – but the potential growth rate of the whole Eurozone.

Martin Schulz may be shaking up German politics, but someone needs to shake up its economics too, once the election season is over. While its economic model has undoubted strengths – including high investment and productivity – Germany needs urgent reforms to deal with its weaknesses in demography, trade and openness if it is to remain wealthy and secure.

Edited by Bill Emmott

- Overall:

- Demography:

- Knowledge:

- Innovation:

- Openness:

- Resilience: